Gastrointestinal Bleeding : Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis & Treatment

Gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding is a serious medical condition that involves bleeding anywhere along the digestive tract, from the esophagus to the rectum. It can range from mild to life-threatening and requires prompt evaluation and management.

What is Gastrointestinal (GI) Bleeding?

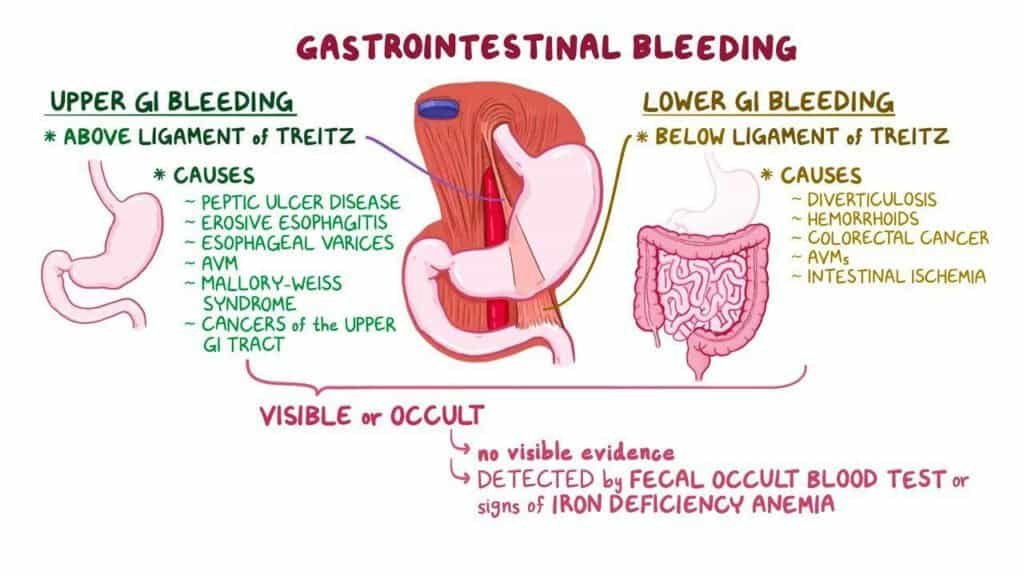

GI bleeding refers to any form of bleeding that occurs within the gastrointestinal tract. It is generally categorized into two types:

- Upper GI bleeding: Originates from the esophagus, stomach, or the first part of the small intestine (duodenum).

- Lower GI bleeding: Involves the lower part of the small intestine, colon, rectum, or anus.

Signs and Symptoms

The presentation of GI bleeding depends on its location and severity. Key symptoms include:

- Vomiting blood (hematemesis)

- Black, tarry stools (melena)

- Bright red blood in stool (hematochezia)

- Abdominal pain or cramping

- Fatigue or weakness

- Shortness of breath

- Dizziness or fainting in severe cases

Syncope or near-syncope, dyspepsia, or epigastric pain may be the presenting symptoms for

bleeding gastrointestinal tract (GIT) and pose diagnostic issues. Patients with a history of

haematemesis, melaena, or haematochezia are more clear-cut.

TABLE 1 Common causes of GI bleeding (frorm Rosen’s Emergency Medicine, 7th ed.)

| Upper GI Bleed | Lower GI Bleed |

|---|---|

| Peptic ulcer | Diverticular disease (diverticulosis) |

| Gastritis | Haemorrhoids |

| Oesophageal varices | Inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s, Ulcerative colitis) |

| Mallory-Weiss tear | Colorectal polyps or cancer |

| Oesophagitis | Anal fissures |

| Duodenitis |

SPECIAL TIPS FOR GPs

- Assess if shock is present (tachycardia and/or hypotension). If it is, call for an ambulance

and transfer to the nearest ED. Set up IV line(s) and infuse saline in the first instance. - If the patient is vomiting blood and conscious, place him in the recovery position and

establish IV lines. - Examine the abdomen for tenderness and do a rectal examination to confirm melaena.

- Establish the risk factors for peptic ulcer disease (PUD): alcohol abuse, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)/steroids including traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), chronic

renal failure, age, and anticoagulation treatment. - Always bear in mind abdominal pulsation and aortic aneurysm.

- Advise the patient to stay nil by mouth (NBM).

- Consider dengue haemorrhagic fever in patients with bleeding GIT and fever or myalgia.

There is a strong association of Helicobacter pylori infection with duodenal ulcers; eradication reduces the risk of both recurrent ulcers and recurrent haemorrhage.

Management

The management of GIT bleeding is essentially as follows:

- To identify shock and resuscitate: correct fluid losses and restore blood pressure/perfusion.

- To identify potentially reversible causes of the bleeding (both systemic, e.g. overanticoagulation, and local).

- To identify physiologic derangements resulting from blood loss (cardiac ischaemia, acute kidney injury, or symptomatic anaemia requiring blood transfusion).

- Assess for the source of bleeding. Bear in mind the possibility of non-GI sources, e.g. haemoptysis or bleeding from the oropharynx. The corollary is that GI bleeding may still be present despite a non-GI source being found.

- Always be aware that aortic aneurysm (aortoenteric fistula) may present as GIT bleeding.

- Always do a rectal examination to establish whether frank melaena is present, or if it is due to local bleeding from the anal canal/perianal area.

- Black stools due to iron treatment are differentiated from melaena by the greenish tinge.

Supportive Measures

Haemodynamically unstable patients

- Patients must be managed in the critical care area.

- Maintain airway. Consider intubation if haematemesis is copious and the patient is unable to

protect his own airway, e.g. depressed mental status from previous cerebrovascular accident

(CVA). - Provide supplemental high-flow oxygen to maintain SpO, at > 94%.

- Monitoring: ECG, vital signs every 5 minutes, and pulse oximetry.

- Perform 12-lead ECG to exclude cardiac ischaemia.

- Establish two or more large-bore peripheral IV lines (14/16G).

- Labs:

- GXM

- FBC, RP, electrolytes, coagulation profile.

- LFT : if the patient is jaundiced.

- Cardiac enzymes : if there is ECG evidence of myocardial ischaemia/injury.

- Infuse 1 L normal saline rapidly and reassess parameters. Arrange for blood transfusion if there

is no significant improvement after the initial fluid challenge. - Insert a nasogastric (NG) tube to free drainage for diagnostic purposes (and to prevent aspiration

if the patient vomits). Do not insert a nasogastric tube if oesophageal varices are suspected. - Insert a urinary catheter to monitor urine output.

- Administer IV esomeprazole 80 mg bolus. This should be followed by 8 mg/h infusion if there is ongoing blood loss such as patient in hypovolaemic shock, if endoscopy shows stigmata

of recent haemorrhage (Forrest Class I and II). - Arrange for emergency oesophagogastroduodenoscopy (OGD).

Haemodynamically normal patients

- The patient can be managed in the intermediate care area though it must be remembered that

the patient may decompensate after his first evaluation due to continued blood loss. - Provide supplemental oxygen to maintain SpO, at > 94%.

- Monitor vital signs every 10-15 minutes and pulse oximetry. Establish at least one peripheral IV (14/16G).

- Perform 12-lead ECG.

- Labs:

- GXM for two units.

- FBC, urea/electrolytes/creatinine, coagulation profile.

- LFT, CE if indicated.

- Start normal saline infusion 500 ml over 1-2 hours.

- Insert a nasogastric tube to free drainage for diagnostic purposes (and to prevent aspiration if

the patient vomits). - Give IV esomeprazole 80 mg. Note that infusion is not required for haemodynamically stable patients with no overt signs of bleeding.

- Upgrade to the critical care area if instability develops.

Specific measures

Oesophageal varices

– Do not insert a nasogastric tube as it may worsen the bleeding!

– Start IV somatostatin 250 µg bolus, followed by an IV infusion of 250 µg/h (successful in up to 85-90% of cases). If somatostatin is unsuccessful in stopping the bleeding, and there is the risk of the patient exsanguinating before endoscopy can be arranged, then the insertion of a Sengstaken-Blakemore tube should be considered. This should be inserted only by an experienced operator.

– Administer IV antibiotic prophylaxis with ceftriaxone or ciprofloxacin to prevent spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.

Others

– Look for scar of previous abdominal aortic aneurysm surgery: this episode of GIT bleeding may represent an aortoenteric fistula, which is a dire emergency. If this is suspected, consult the general surgical registrar and cardiothoracic registrar.

Disposition

Stable low-risk patients

- Patients with small amounts of GI bleeding may be admitted to the observation unit for further treatment/endoscopy provided the following conditions are met:

For upper GI bleeding:

- Age <65 years.

- No significant comorbidities.

- No hypotension (systolic blood pressure >110 mmHg), postural hypotension or tachycardia.

- Haemoglobin (Hb) >11 g/dL for males or >10 g/dL for females.

- No overt GI bleeding, e.g. haematemesis or fresh melaena.

- The patient is reliable.

- No stigmata of recent haemorrhage on endoscopy.

For lower GI bleeding:

- Directly visualized haemorrhoidal bleeding clinically assessed to be self-limited.

- An otherwise healthy individual with normal vital signs.

- No comorbidities.

For all other patients, consultations for admission to either General Surgery or Gastroenterology depending on institutional practice.

The Glasgow-Blatchford bleeding score (GBS)

-> To identify patients presenting with upper GI bleeding to the ED who can be safely discharged and managed safely as outpatients without urgent need for endoscopy or monitoring. Patients must fulfil the following criteria:

- Blood urea <6.5 mmol/L.

- Hb >13 g/dL for men, >12 g/dL for women.

- Systolic blood pressure >110 mmHg.

- Pulse <100/min.

- No melaena or syncope.

- No hepatic disease or cardiac failure.

NOTE: For prediction of need for intervention or death, the GBS was superior to the full Rockall score (ROC of 0.90 versus 0.81). GBS scoring reduces admissions for this condition, allowing more appropriate use of inpatient resources. Rockall scoring incorporates endoscopic diagnosis which limits its use in EMD as emergency endoscopy is usually indicated for patients with major bleeding.

Intermediate or high-risk patients

Consultations for admission to either General Surgery or Gastroenterology depending on institutional practice.

📝 References :

- Lau JY, Sung JJ, Lee KK, et al. Effect of intravenous omeprazole on recurrent bleeding after endoscopic treatment of bleeding peptic ulcers. N Engl J Med. 2000; 343(5): 310–316.

- Westhoff J, Holt KR. Gastrointestinal bleeding: An evidence-based ED approach to risk stratification. Emerg Med Pract. 2004; 6(3): 1-18.

- British Society of Gastroenterology Endoscopy Committee. Non-variceal upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage Guidelines. Gut. 2002; 51(SuppIV): iv 1-iv 6.

- Habib A, Sanyaj AJ. Acute variceal hemorrhage. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2007; 17: 223-252.

- Stanley AJ, Ashley D, Dalton HR, et al. Outpatient management of patients with low-risk upper-gastrointestinal haemorrhage: Multicentre validation and prospective evaluation. Lancet. 2009; 373: 42-47.

- Pallin DJ, Saltzman JR. Is nasogastric tube lavage in patients with acute upper GI bleeding indicated or antiquated? Gastrointest Endosc. 2011 Nov; 74(5): 981-4.